As reported last week, the respected Swedish plough and implement manufacturer, Overum Industries, unfortunately finds itself in bankruptcy and the factory remains closed.

As the situation stands, it is reported in the Swedish press that the company is in the hands of a receiver who has it for sale with the closing date for tenders being October 20.

Naturally, it is the hope of all concerned that a buyer is found, for there are up to 70 jobs on the line at the factory plus all the dealers who rely on the sale of its products as part of their income.

A long-term going concern

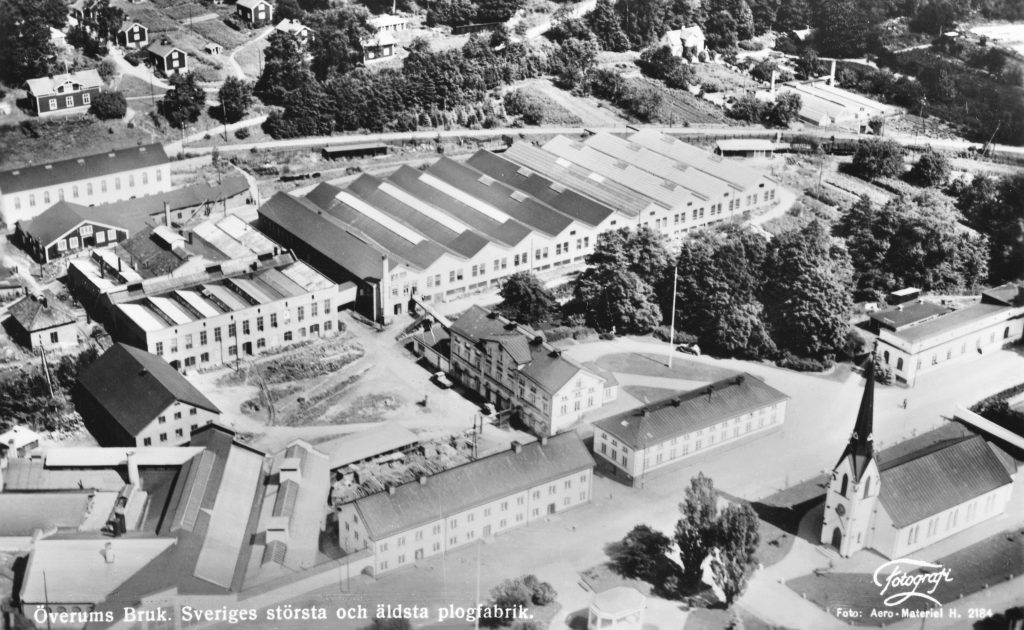

However, viewing Overum through the lens of its present difficulties obscures its long proud history which stretches right back to 1654, a time-span that no other present day plough manufacturer can match.

Lemken come the closest, being founded in 1780, while Pottinger, Kverneland, and Amazone were all formed between 1871 and 1883.

This is not the whole story, however, for Agrolux ploughs – which are now a part of Overum – was formed even earlier than its parent company, in 1649.

Yet ploughs were not the focus of the fledgling business – it was, just like the other Nordic countries, the arms industry which encouraged the first attempts at industrialisation.

Arms race

At the very start lies a figure by the name of of Louis De Geer, who is regarded as the father figure of Swedish industry.

Of Walloonian heritage, De Geer was ennobled by the Swedish king in gratitude for his help in various conflicts.

He had established a successful trading empire, which came to enjoy a monopoly in the Swedish iron and copper trade thanks to these efforts, and ended up taking Swedish naturalisation.

As part of his business activities, De Geer had founded an ironworks in Norrkoping which was then entrusted to the stewardship of another Walloon emigrant, Henrik De Trij.

De Trij was already the owner of a workshop in the area and had amassed some wealth himself. In partnership with two brothers-in-law by the name of de Besche, De Trij went on to establish a blast furnace at Overum, having been granted a royal charter to do so.

It was at this point that the business known as Overums Bruk came into existence.

Limited resources

Casting cannon barrels was the mainstay of the business for at least the following 150 years and the foundry become the major supplier of guns of all sorts to the Swedish crown.

It was not all plain sailing however, as the company had to compete with other businesses for coke produced in the local forests.

It was coke, along with water wheels, which underpinned Sweden’s early industry, as the country did not have the reserves of coal that powered the industrial revolution over in Britain.

There were also changes in ownership and management over the years, culminating in Johan Carl Adelsward purchasing Overum in 1816.

By then, production had greatly diversified and cannon were no longer the staple of the foundry as a greater variety of products were manufactured.

Yet it would appear that the company had lost its impetus until the appointment of Carl Petter Spanberg as works foreman in 1850.

New era

Spanberg was obviously a fellow in demand, for the Ultuna Agricultural Institute had employed him as a toolmaker.

When he was offered the position at Overum, the institute countered by offering him promotion, but Spanberg decided that the commercial sector would give greater scope to his ambitions.

The following year, in 1851, the production of ploughs began, with 94 being produced that year, 20 of which were sold to persons of standing in neighbouring regions.

It was about this time that cannon production ceased altogether and the plough workshops become the mainstay of the business, employing 78 of the 184-strong factory workforce in 1862.

Other assets

Although Overum might be considered a purely engineering company, it was quite self-sufficient in its raw materials, owning iron ore mines and forests for coke production as well as the timber for its ploughs.

The company also possessed land which it farmed itself, but it was the large areas of forestry under its ownership that were to attract the interest of a saviour at a later date.

The agricultural business had taken off and was performing well for the company for, by 1862, plough production had reached 2,669 units along with parts, plough bodies, and 590 other implements.

In 1854, the company produced its No. 9 plough, which is considered to be a copy, or at least a development of, an unspecified American model. This went on to be regarded as the archetypical Swedish plough.

English imports

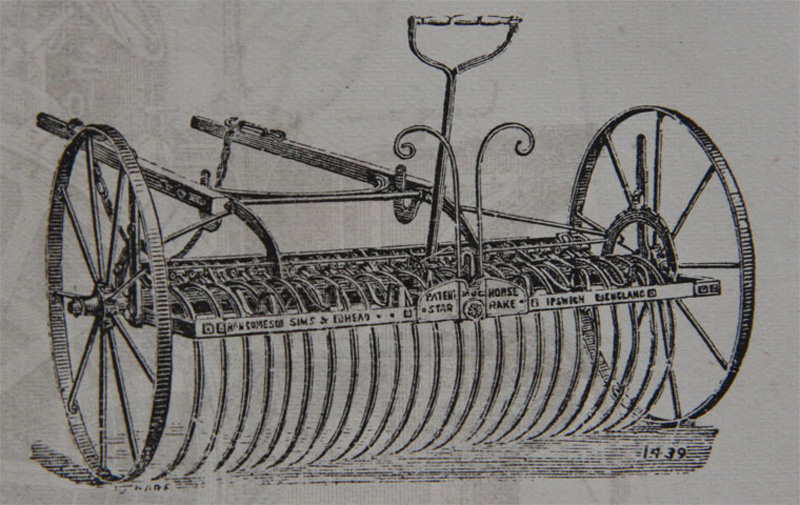

In the catalogue for 1861, there was also a Plough No. 1, which is described as being based on an English model, while alongside it are listed items such as Allen’s Harvesting Machine, Ransome’s tedder, and other English brands of the time.

These products are described as being produced by Overum, most likely under licence, yet there remains the possibility that the company was acting as an importer and was distributing them alongside its ploughs.

The English connection was reinforced with the sale of Overum Bruk to an English investment company in 1872 that was concerned about Overum’s presence in the Russian market.

This activity posed a threat to other companies in the investment company’s portfolio, and Overum was later floated off as a separate limited company in 1882, with the shares remaining under the same ownership.

This arrangement lasted until 1918 when it was once again sold, this time to Svenska Tandsticks AB, or Swedish Match Company, whose owner Ivar Kreuger was more interested in the forestry than the factory.

Pressure of competition

Despite its earlier success, the company suffered a good a deal of competition with 31 other implement manufacturers being active in 1865.

From then on, plough production fell in importance, especially during the decline in farm fortunes of the 1880s.

When brighter prospects returned, Overum was not able to compete successfully with companies such as Norrahammar and by 1910 it had only 5% of the Swedish plough market, down from 35% in 1836.

Exports had also declined: in 1882, 4,515 ploughs were sold to Russia, by 1903 that had dropped to 315.

This general air of bumbling along lasted until 1920 when, after a large investment by Kreuger and the appointment of Carl Sundberg as its manager, the company introduced its first tractor-drawn plough.

This product restored Overum’s fortunes to such an extent that by 1928 it was able to purchase the plough manufacturing interests of its fiercest competitor, Norrahammar, establishing Overum once more as Sweden’s premier plough manufacturer.

From this brief account of Overum’s early history, we can see that it has overcome adversity before and thrived again under new ownership after hefty investment.

History does have a habit of repeating itself: there are many who will be hoping that it does so again with regard to Overum Industries.