Agriculture depends on a large and thriving supply industry to keep its everyday operations going, and in a country where livestock predominates the provision of animal feed, it is an important segment of that business.

Feeding stock the by-products of milling cereals is as old as milling itself, although the inclusion of concentrated protein and carbohydrate sources would have come later, a practice that was accelerated by the growing understanding of animal nutrition.

To supply the growing demand for both flour and animal feed, mills were built across Ireland.

It is estimated that at one time, there were at least 7,000 working in the country.

One of those was Riheen Mill at Castle Haven, in the far reaches of west Cork.

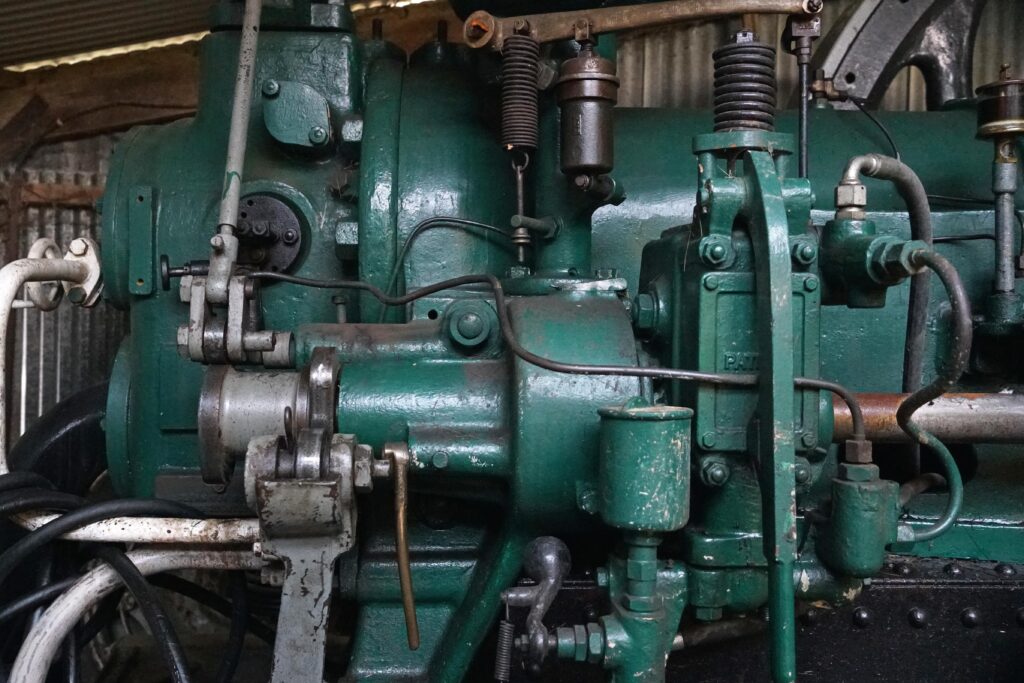

First recorded in 1697, the mill was driven by water until the early 20th century when the large undershoot wheel was replaced by a pair of Crossley heavy oil engines.

At some point, the mill closed down and the site and all of the machinery lay abandoned, including the two engines.

All of this changed around 10 years ago when Derry and Bart Desmond from Kinsale, Co. Cork, decided to rescue them and bring at least one back to working order.

Bit by bit

This was no easy task, as the main mill building was in an advanced stage of dilapidation.

To avoid breaking a hole through the walls, each engine had to be dismantled and craned out in pieces.

The upside of this operation was that by doing so, the approximate weight could be calculated thanks to the crane being equipped with a weight indicator.

The engine frames and cylinders weighed in at 4t each, and the flywheels were also 4t apiece – bringing the weight to 8t for each unit.

Back at the family farm, all of the parts were cleaned and reassembled on the one that was to be restored, with Desmond, a marine engineer by training, being full of admiration at how smoothly it went.

Getting it back into running order was one task, getting it to actually run was another, and here, a lot of trial and error was involved to set the single injector to run on diesel, rather than heavy oil.

Thankfully, Crossley’s approach to making engines was to have a good range of standard parts which were then assembled to suit the power requirement and fuel the engine was destined to run on.

Everything on these larger Crossley models is big, simple and basic, so there was no need for any fiddling with a screw driver, just the adjustment of the injector spring and governor.

Heavy, or marine oil is the stuff that is left behind when all of the lighter factions have been distilled from the crude.

Being the leftovers, it tends to be thick and viscous, and therefore requires heating before it can be injected. It is also cheap.

This made it suitable only for marine and stationary applications for the heating apparatus is heavy and cumbersome, taking the form of a water bath through which the exhaust is blown before being passed through a heat exchanger, making the heavy oil thin enough to be injected.

Derry and Bart intended to transport the engine to shows so the sensible route was to adjust it to run on diesel, which many of this type did anyway, although they tended to have the injector at the end of the cylinder, rather than at the side.

Firing up

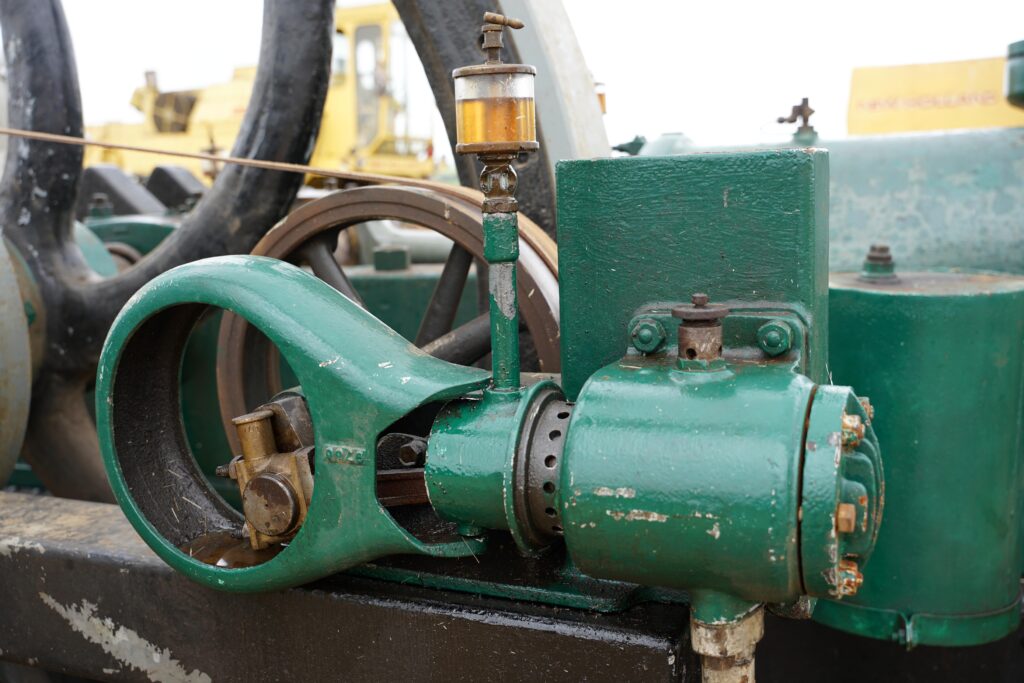

Whatever the fuel, compressed air held in a riveted tank at the rear was fed by its own compressor.

On heavy oil models, the air was led to the end of the cylinder.

On diesel models it was led into the side, and the injector was at the end. Therefore, having this engine run on diesel is not technically correct, but it is far more convenient.

The first stage of the starting sequence is to bring the piston to top dead centre.

Compressed air is then let into the cylinder, causing it to turn the crank and the diesel injector then takes over for the next firing stroke, starting it immediately now that it is tuned.

There are no hot bulbs, blow lamps or cartridges, it just fires up and runs according to Desmond, and once going, it will only sip at the diesel, needing only a few litres to run at a show for a day.

Presently, the actual power output is not known, the brothers estimating it to be somewhere around 45-50hp.

Crossley, the company

The Crossley company was formed in 1867 by Frances Crossley on the purchase of an existing engineering firm in Manchester.

Soon after, he was joined by his brother William, and they then acquired the rights to manufacture the Otto four-stroke engine in 1876.

This was followed up in 1896 by a licence from Rudolf Diesel to produce his engines, the first units appearing two years later.

The idea of compression ignition engines was not new, as Herbert Akroyd had patented a design in 1890 and went on to sell 45,000 engines by 1904.

However, Ackroyd preferred to make the engines himself while Rudolf’s business model was to licence his design, yet it was the Ackroyd method of straight injection of fuel into the combustion chamber that prevailed and it was this system that we saw in this particular Crossley engine.

Crossley engines eventually became part of Rolls Royce Industrial Power Division in 1988.