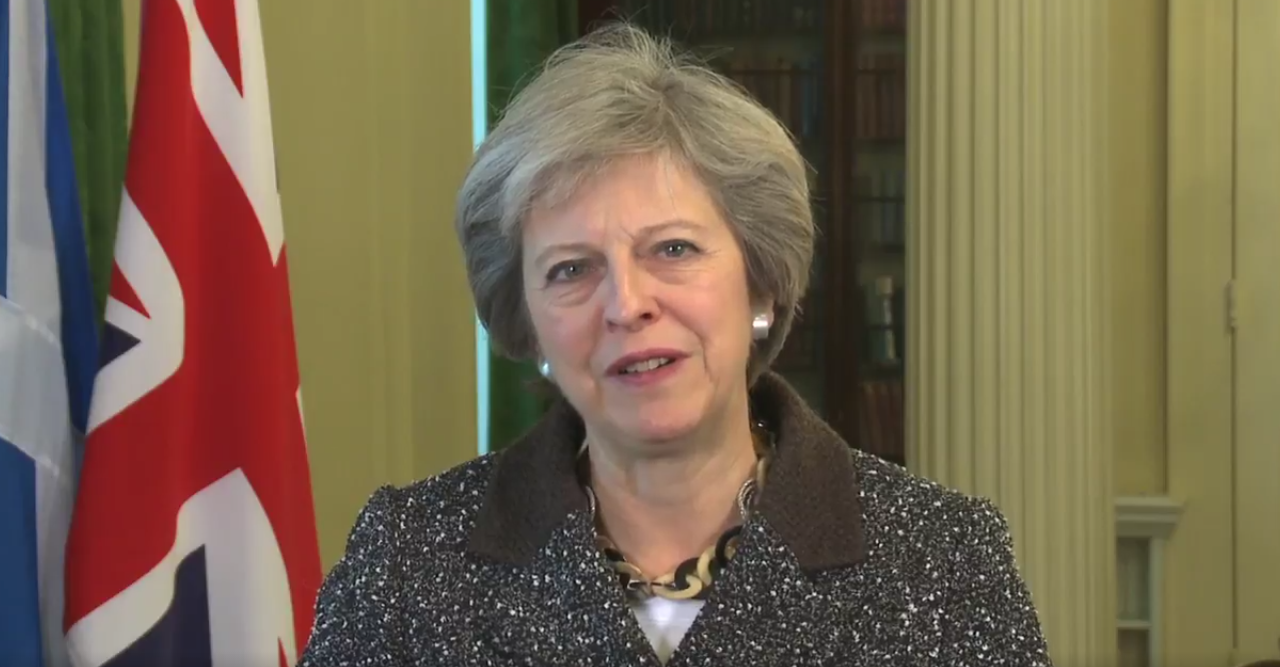

They say that timing is everything in life. And where Theresa May is concerned, the fact that she has left the agreeing of the draft Brexit package with EU officials until such a late stage in the day leaves the UK with not much option but to back what’s currently on the table or fall-out of the EU in a totally ill-fated manner.

Who knows? This might well have been the plan all along.

The reality is that the Prime Minister could have gotten the Irish backstop deal over the line weeks ago with the help of Michel Barnier and his team of EU bureaucrats.

The history books may well show that the Prime Minister and the EU, actually, orchestrated the series of events that we saw unfolding over the past few days many weeks ago.

The proof of the pudding where this is concerned will focus on the EU’s reaction to any further pressure that may come for Brexiteers within the Tory party for further changes to the agreement.

If the line from Brussels remains that of refusing to enter into further substantive negotiations then it’s pretty obvious that the EU-27 has gotten what it wanted from the process. And the same may well hold for Theresa May.

Her fight back is under way. Recent days have seen many leading figures within the Conservative party calling for MPs from all parties to act in the national interest. The next stage in this process may well be calls for the establishment of a de facto ‘government of national unity’, specifically to get the Brexit deal over the line.

But let’s focus on what’s in the national interest for farmers.

The fundamental question now arises: does the deal currently on the table offer hope to the UK’s farming sector?

One very positive aspect to the debate of recent days, from an agri perspective, has been the talk of potential food shortages should the UK fail to reach an exit deal of any kind with the EU.

Media reports of this nature bring home the fact that the UK is a net importer of food and, as a consequence, more should be done to bolster our indigenous farming sectors.

In the short term, any transition deal struck between London and Brussels should help ensure that the UK’s current import and export relationships with the EU are maintained, at least until the beginning of 2021. This will be good news for the sheep sector, which is heavily reliant on exports to countries like France.

But looking to the long term is all about sorting out a deal between the Department of the Environment, Food and rural Affairs (DEFRA) and UK agriculture as a whole.

And it’s all about money. Farming needs a realistic support budget for the future. Primary producers cannot survive on the back of the commercial returns currently generated by the farming and food chain. The entry point for discussion, where farm support is concerned, is the current commitment given by Brussels to the UK.

It must be emphasised, however, that this is only the starting point. British agriculture needs a realistic support budget for the future, one that will allow it to grow on a sustainable basis.

If this is not received then Brexit will prove to be a bad deal for UK agriculture, irrespective of whatever final arrangements are agreed between London and Brussels.